At the Merida R&D headquarters near Stuttgart, we were given the opportunity to take a glimpse of the complete development process of the new One-Twenty, meeting its creators and discussing the ins-and-outs of bike design.

I have been riding bikes since 2006, publishing in Bikemag for over 7 years, made numerous visits to trade shows and production facilities, so I thought I have seen everything. Not so. In the course of a trip to the European development center for Merida bikes in Magstad this September, I finally had the chance to conduct an unhampered conversation with the staff without any taboos. Yes, I could ask anything, and I got honest and full answers to all my questions. Are you interested?

Annual product presentation events – such as the recent Merida test camp held in Ruhpolding – provide a great opportunity to get familiar with the new crop of bikes, but unfortunately there very few technical details available at the time. So the journalist can only tell readers how the bikes look and ride, but is unable to give a true insight into the details of the new developments. Of course, I try to enquire about the technical background from the company staff on site, testing their patience with my engineering-related questions. In most cases, they repeat the general information their marketing team has issued, then ending the sentence by saying: “Our engineers are among the best in the industry!” At some product presentations there is a genuine engineer on site, but most often this person has a specific task at the R&D department that is vastly different from the details I’m enquiring. So I end up getting no wiser after a lengthy dinner table conversation…

It’s no secret for our readers that I had worked as a development engineer in the bicycle industry for two years. During this period there was only one occasion that I can recall when I got in touch with the media. In general, engineers rarely talk directly to journalist, or the public at large. By default, the marketing department handles this side of the business, not the ones who have all the answers!

This rater lengthy introduction tries to give an insight into why I was delighted to be given this special opportunity by BikeFun Hungary. I had the chance not only to visit the Merida’s European R&D center and learn about the development of the brand new One-Twenty, but also to have an open, unrestricted discussion about the process with the actual people, who worked on the project. Unfortunately I had an accident just before the trip, so it was quite uncertain that I could make the journey. But in the last minute the doctor deemed the wrist operation a success, so I was free to attend.

I was met me at the Stuttgart Airport by Simon Oppold who heads the marketing department for the entire Merida & Centurion group. He has nearly 20 years of experience in the bicycle industry. The airport parking lot was a good representation of what this part of Germany is renowned for: for example, next to Simon’s car was a Porsche GT2 RS in a “John Player Special” design! On the way to his office Simon talked about the difficulties of finding qualified employees in this region: there is a high demand on the job market, new graduates – especially engineers and IT professionals – are immediately recruited by the large companies like Bosch, Mercedes and Porsche. The industry’s involvement entails an exceptionally high standard in education, creating a hotbed for a professional environment. This was the place where one of the world’s leading bicycle brand felt obliged to establish its European R&D center. The Merida division in Magstad has approximately 15 employees, a team is headed by Jürgen Falke, and their task is to develop the models the Taiwanese brand launches on the world market. Among the team members is a Hungarian engineer, Csaba Röszler, whose insights into the development process were documented in a previous Bikemag article.

Immediately after arriving at the Merida offices, Simon took me on a tour of the R&D center. We walked through the whole building, starting on the top floor where the engineers and industrial designers work. Jürgen Falke’s office is located in the center, serving as a hallway between the engineers, designers and the marketing executives. In addition to these offices, there is a presentation hall and a boardroom on the upper level, with fully-equipped a test lab located at the end of the corridor. The latter serves for carrying out static tests of the prototype frames and random tests from production samples.

The equipment in the lab is provided by the Zedler Institute, a name that serves as a reference for bicycle-specific measuring and test equipment worldwide. The frame geometry jig and a 3D printer in the lab is often used to facilitate modelling during product development. The latter is used to create smaller objects, such as dropouts and suspension linkages.

Merida R&D –3D printed prototype components facilitate the development process

The lower floor houses the rest of the marketing department, including the contact person for the World Tour Bahrain-Merida team as well as staff responsible for accounting. There are additional board rooms and smaller storage areas, and in the basement we find a fully equipped workshop with a full-time and a part-time employee assisting all matters concerning fabrication and repair. These two members of the staff are responsible for assembling the prototype bikes along with the maintenance of the fleet of bikes used for testing.

Merida R&D – Development Engineer Roman Braig and Product Manager Benjamin Diemer proudly present the new One-Twenty

From here on I was entrusted to the head engineer Roman Braig and the product manager Benjamin Diemer to provide me with the details of the new One-Twenty’s development process.

In the first step of development all requirements of a future model are defined. This is a multi-element equation, where many factors play a role in the decisions, such as main application (type of riding), industrial trends, feedback from dealers and end-users and of course brand image. The key requirements for the One-Twenty were the following: 29″ wheel size, low step-over, Trunnion Mount shock mount compatibility and Full Floater kinematics. Given that the development process can take as long as 2-3 years, such meticulous preparation might seem a difficult task at first, but Benjamin explained that frequent contact with suppliers help a lot in planning for the future. Even at this very early point of the development process the team makes decisions concerning frame geometry, and first 3D freehand drawings are made in accordance with the company’s brand image.

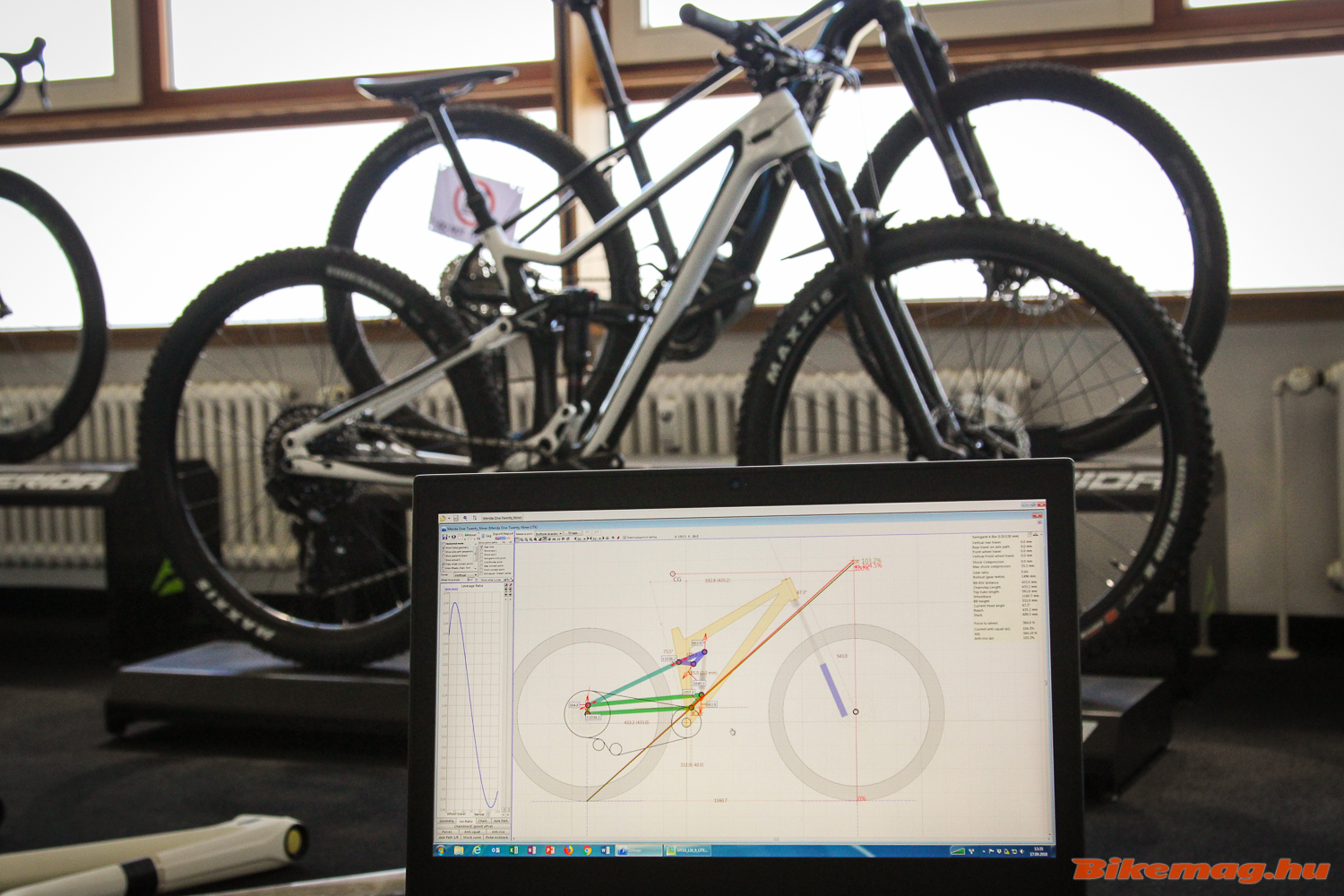

This is the point where proper engineering work begins. In the first phase of development, Roman harmonizes two fundamental things: the suspension kinematics and rotation points. These are optimized by an application called Linkage, while 3D solid state planning is performed in CREO. There are obviously a lot of back-and-forth cycles, since these sub-processes are highly interrelated.

Why does the team cling so strongly to the Full-Floater design? This is a four point linkage system which employs a faux bar linkage driven single pivot, best described as an ingenious way to combine the advantages of both the single-pivot and multi-pivot linkage systems. The lower end of the strut is not permanently attached to the frame, it’s connected to an extension of the chainstays. According to Roman, the main reason for sticking to this suspension design is that Merida have accumulated a lot of experience in this field, and a transition to a VPP system would have greatly elongated the One-Twenty’s development. Moreover, the Horst-Link (FSR) design has been a great success for another brand in which Merida is part-owner, and the two companies have probably made an agreement to allocate the available technologies and know-how between the brands.

The Full-Floater system is a tried and trusted design, which is certainly a great advantage. The Linkage application allows Roman to analyze even the smallest design changes in detail. He wants to test how the suspension reacts to pedaling and braking forces, and how much these could be filtered from the character of the suspension travel. In addition, the engineer is constantly monitoring the leverage ratio (how much the rear wheel travels for the given shock movement), and not only for the actual state of progress, but the entire travel range. This latter is sometimes referred to as a progressivity curve of the suspension design.

If you are satisfied with the result of the first phase described above, the 3D model computer model is turned into a genuine frame. Once it’s printed and assembled, the product manager checks the geometry and design parameters, if all looks spot on, then he places an order for the first prototype to be manufactured. It’s an immense to the R&D team to have the Taiwanese parent company available for this phase, since it makes negotiating with all the individual suppliers unnecessary. So not long after the order is completed, the first sample arrives from one of the largest manufacturer of bike frames in the world!

In this case we are talking about very-very expensive aluminum frame, as it has to be custom manufactured with the individually CNC machined linkages, dropouts and yokes. The molding tools needed to make the respective frame tubes are still in the planning phase. The final product sample will look somewhat different from what the R&D team envisaged, but this “monster of a frame” is perfectly suitable for checking on geometry and suspension design in practice. Even the assembly of the prototype frame into a complete bike will provide the team with a lot of feedback. Once the bike is ready to roll, it will be given to testers, often the team will ask a brand ambassador like José Antonio Hermida Ramos or the Spanish enduro champion Toni Ferreiro. The testers take the prototype on some truly demanding rides. If their feedback turns out to be positive, the development takes another step towards production.

Then it’s the time to order the final pre-production prototypes. They now have the final tube shapes, but some technical details still need to be refined. In case of the One-Twenty, the team realized that two Torx keys were needed to disassemble each pivot in the suspension linkage. When the nut was rotated, the screw turned with it, requiring a second tool to fix it in place. As this makes both assembly and servicing more difficult, Roman designed a special flattened nut to hold one of the pieces in place. After this modification assembly and disassembly of the linkage needed only a single Torx key.

Since we are in the just final phase before full production, the hydroform tubes, the forged yokes and the dropouts are the actual final production versions, so engineers can make a final check on the frame in the test lab. This involves static and dynamic tests: the former takes place in Germany measuring the stiffness of the head tube, the bottom bracket area and the rear dropouts, as well as predicting vertical compliance, in other words the expected comfort and behavior of the bike. These numbers provide good feedback. If for some reason the engineering targets are not fully achieved, the frame cannot be manufactured at the designed weight, additional prototype iterations are needed. In case of the One-Twenty – following some tweaks to save a few more grams – the 3rd prototype finally reached all the targeted goals.

The dynamic and fatigue tests for the production frame are run in Taiwan, but German engineers are also present to evaluate the results. The test procedure involves more than just programming the load and number of cycles specified in the ISO 4210 test protocol: in most cases Merida specifies further testing with much higher loads and cycles. Testing is often continued until complete failure to see the true limits of the frame. There is a wealth of information coming out of Merida’s procedure, allowing the manufacturer to determine the expected durability of the frame in question, as well as aiding developments in the future.

At this point dozens of riders have already tested the bike in actual conditions, and now the manufacturer is working together with the shock suppliers to fine tune the kinematics of the production model based on the rider feedback. Both the front fork and the rear shocks may get small modifications from the base model to enhance suspension performance. In this phase the part specifications and the colors are determined so the bike is ready to be presented to the market and the media. First and foremost the distributors will have the chance to see and try out the new model, then the media will be supplied with the finalized production version for testing and review. Minor modifications may happen even after this stage. These are often referred to as “running changes”, and are quite common in car manufacturing as well in the bike industry. Most consumers are not aware of such minor details. In case they take their car to a service center, it may turn out that the model has a different part installed compared to the specification.

The outlined development process is more or less the same for carbon and aluminum frames, but in case of the former, instead of solid state modeling, the design involves surface modeling carried out by an industrial product designer. The greatest challenge for carbon bike frame technology at the moment is that 99% of the frames are made using “compression molding” which requires a one-off fabrication a very costly production mold for each frame size. So in the bike industry it is always worth to double check all details before full production!

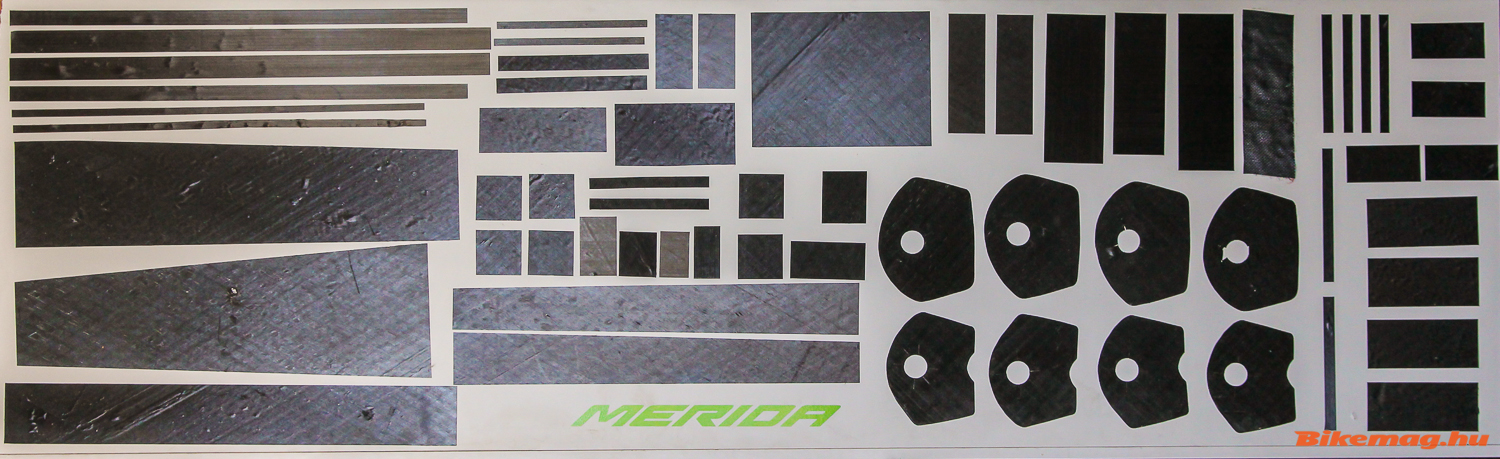

Merida R&D – the 3D-printed plastic prototype

So the R&D team takes an extra step by creating a 3D-printed plastic prototype to make sure everything is spot on, in order to avoid expensive mistakes. These are not functional frames, they cannot be ridden, but all components will be assembled onto these printed plastic “dummies”. Mountings, spaces and shapes will be measured and re-checked. In case of the One-Twenty, the 3D printed frame has been tweaked in some places with clay, which resulted in better functionality and visual shapes. Once everything is deemed ready, all production-related responsibilities are handed over to Taiwan. They start then start the process by creating a plybook.

During my visit to the Merida R&D center I got the impression that Roman and Benjamin are highly motivated by their work. This feeling was underpinned by the brief test ride we did on the One-Twenty 8000. We set off on the trails around Stuttgart, where I had a chance to experience the true character of the bike as well as the development team’s great enthusiasm for it.

The 130 mm fork turns the One-Twenty into a genuine trail bike, it rides the best on fast descents, and loves gradual turns at speed which requiring the rider to lean into them. It behaves like a serious downhill bike which need to be driven from the whole body. The suspension design also enables aggressive riding, and the 29″ wheel size offers very good traction. The pace I could sustain was limited by the recent wrist operation, sometimes I was not able to charge the front wheel enough into the turns. The suspension system was also quite effective on climbs. When I intentionally remained in a standing position, there was still almost no suspension bob from the system. Equipped with single chainring 1×12 shifting, the bikes provided an adequate range of gears, even for riders of average endurance. We could easily get to the top of a mountain, and the 12.6 kg total weight including the “dropper” seat post is quite favorable in this market segment. The One-Twenty can also serve double-duty as a marathon rig, especially if the rider prefers the experience of the descents over absolute climbing speed.

During our dinner, in front of a plate of Maultaschen, we dove into the discussion about a number of topics, ranging from the housing prices in the Stuttgart area, through local food specialties, to everybody’s favorite topic, cars. But no matter how much of a tangent the conversation went, we always returned to cycling. This is no surprise, since everybody at the table works in the bike industry, so our whole life revolves around bicycles. Over the past 10 years Merida has made great strides in developing industry-leading technologies as well as acquiring an exclusive brand image. After my visit to its European R&D center I have no reservation about either.

Hungarian distributor of Merida bikes – BikeFun.hu

http://bikefun.hu/

BikeFun Hungary Facebook page

https://www.facebook.com/bikefunhungarykft/